THE WHALE SHARK

CURRENT CONSERVATION INITIATIVES

REPORT

By

Brad Norman (July 2000)

THE WHALE SHARK (Rhincodon typus)

| Description | Ecotourism | Minimising Impacts | Latest Events | Where to Next | Contact |

DESCRIPTION

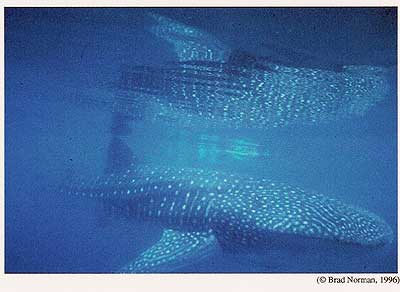

The whale shark (Rhincodon typus) is the largest living shark. It is

one of the three filter-feeding species of shark, with a broad, flattened head

and minute teeth. It also has a distinctive patterning of light spots and stripes

over a dark background, fading to a light colour on the underside. This natural

camouflage allows it to 'blend' into its surroundings when viewed from any angle

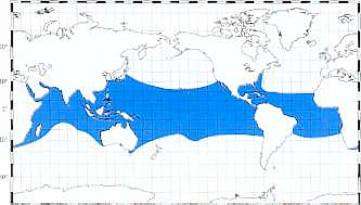

Distribution

Whale sharks are found in all tropical and warm temperate seas except the Mediterranean,

with a range typically between latitudes 30 degreesN and 35 degrees S. They

are known to inhabit both deep and shallow coastal waters and the lagoons of

coral atolls and reefs, frequently in surface sea-water between 21 and 25 degrees

C.

(from

Last and Stevens, 1994)

These animals are found at varying locations throughout the world's oceans at different times of the year. Many are within close proximity to Australia (India, Indonesia, Thailand, Philippines and Taiwan). At several of these locations, the increase in whale shark prevalence appears to be related to seasonal food pulses, particularly at Ningaloo Reef, Christmas Island and near the Great Barrier Reef. The sharks are not usually sighted in large numbers and are regarded as fairly solitary.

Ecology

and Life History

The whale sharks are ovoviviparous - they produce live young (eggs hatch inside

their twin uteri). This was only recently discovered (1996) when the only pregnant

female ever studied was harpooned off Taiwan and contained approximately 300

embryos (total length between 48 - 58cm). There have, however, been no long-term

studies which have produced validated growth rates, age at maturity, maximum

age, the length of gestation, localities of birth, and frequency of reproduction.

These basic questions require further study.

While few predators of the whale shark are known, juvenile specimens have been reported from the stomachs of a blue marlin and a blue shark. Several whale sharks from Ningaloo Marine Park (NMP), Western Australia possess scars that may be the result of shark attack at an early age. This species is likely to be vulnerable at an early age, their rapid increase in mass beyond birth appearing to be their main defence later in life. It is pressure from fishing and accidental vessel contact which may be their greatest threat.

The whale shark is a filter-feeder. It is believed to sieve zooplankton as small as 1mm in diameter through the fine mesh of their gill-rakers. However, unlike the megamouth and basking sharks, the whale shark does not rely on forward motion but can hang vertically in the water and 'suck' food (see below).

Brad

Norman, 1996

Although they are closely related to the largely bottom-dwelling sharks, their habit of basking at the surface at unique and easily accessible locations has enabled us to learn more about this magnificent species. It has also provided tourists with the opportunity to comfortably swim alongside the largest living shark.

ECOTOURISM AND SHARK BEHAVIOUR

The ecotourism industry revolving around the whale sharks at NMP was fully established by 1993. It has burgeoned to become a huge economic boon to the economy of the region - with investment by those involved in this industry as high as $4.7 million per annum. Research was initiated to determine the impacts of ecotourism activities in the whale shark resource at NMP.

Management and Regulations

Tourists and the whale shark ecotourism industry operators are regulated by

guidelines established through discussions by industry and the management agency

(CALM). Some regulations relate to:

the

minimum distance permitted between snorkellers and shark,

a ban on touching the whale shark,

the minimum distance permitted between vessel and shark,

the maximum number of swimmers in the water interacting with a shark,

a ban on use of flash photography and motorised propulsion units,

the maximum period of interaction between tourists and shark.

In late 1994, Brad Norman took up a scholarship at Murdoch University to undertake arguably the most intensive study on the largest and one of the least harmful sharks. Although this work was primarily concerned with the effects of ecotourism on the whale shark resource at Ningaloo Reef, it became immediately apparent that this provided an excellent opportunity to collect important information on aspects of the biology and ecology of Rhincodon typus.

Support was received from the tour industry operating within NMP, as was assistance from government departments, the local management agency, research institutions and the many volunteers from the local, conservation and tourist community.

|

|

|

| Aerial

surveys (volunteers) |

Vessel

surveys (volunteers) |

Biology and Behaviour

During

the initial stages of the study at NMP, the set of behaviours commonly displayed

by whale sharks was established. The activities of sharks, tourists and industry

throughout whale shark/tourist interactions were observed and recorded. A comprehensive

list of findings are available in the subsequent thesis:

Norman, B.M. (1999). Aspects of the biology and ecotourism industry of the

whale shark Rhincodon typus in north western Australia. Master of Philosophy

Thesis, Murdoch University, WA.

Significant facts concerning the sharks that visit the northwest of WA include:

This study has served to provide baseline information on this species and the associated tour industry. It has established a continuous data set, which can be updated each successive 'season'.

MINIMISATION OF ECOTOURISM IMPACTS

From the results collected throughout the project, the following practices are recommended at NMP (and at other international ecotourism destinations) to ensure that ecotourism adheres to the 'look don't touch, don't impact on nature' principle:

These simple changes may ensure sustainability for the lucrative whale shark ecotourism industry in Australia (and abroad). It will have the added benefit of reducing the level of pressure on the sharks and enhancing the public's perception of well-managed ecotour operations.

As an invited speaker at two recent conferences, Brad Norman presented results collected during the study at NMP and Christmas Island since 1995.

National Coastal Conference (Melbourne)

Australia's National Coastal Conference (Coast to Coast 2000), Melbourne

Convention Centre (March)

The whale shark ecotourism industry at NMP was discussed, with particular reference to the successful sustainable management regime in place. This meeting provided an outstanding opportunity to bring to the attention of the broader public, the conservation plight of the whale shark, while highlighting the unregulated hunting pressure imposed on this species in nearby Asian countries. Special emphasis was placed on the need to collect further important information to assist with global protection through collaborative efforts of government, industry and private groups. Excellent feedback was received from attendees and the study gained substantial exposure as a result of several subsequent media interviews.

International

Shark Conference (Mexico)

The largest international shark conference (American Elasmobranch Society)

La Paz, Mexico (June)

A special symposium was dedicated to the whale shark. The conference attracted researchers from around the globe, and provided excellent networking opportunities - (currently being explored) for future projects on this species. Examples of results presented by participants include:

In his presentation, Brad Norman again argued the need for an international collaborative approach by industry, managers, researchers, and conservation and other interest groups to gather important data on the whale shark. This initiative received broad support and was seen as necessary to assist with the worldwide conservation of this species.

The author had previously been invited to prepare a Species Report outlining the present knowledge and conservation concerns for R. typus. At a special meeting of the IUCN Shark Specialist Group convened at the Mexico conference, it was confirmed that the IUCN conservation status of this species was amended to 'Vulnerable'. This will soon be published in the 'Red List of Threatened Animals ' (IUCN 2000).

To enable trade in whale shark products to be adequately regulated, R. typus was nominated on Appendix II of CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) in April 2000. Although rejected at that time, Australia has since nominated this species on CITES-Appendix III. This will facilitate cooperation between other CITES Parties (i.e.countries) to control trade in products from this species, and facilitate a stronger nomination for Appendix II in 2002.

To encourage greater awareness by the Australian government and general public, AMCS WA has endorsed a nomination prepared by ECOCEAN (Environmental Consultants), to list the whale shark on the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act, which replaces the current Endangered Species Protection Act. Although fully protected in Western Australian waters under the CALM Act, the Wildlife Conservation Act, and the Fisheries Management Act, inclusion on the EPBC Act will protect the whale shark in all Australian waters and assist efforts to establish greater protection for this species in the Australian-Asian region. This is extremely important - as unregulated hunting in nearby countries (see below) may have a devastating effect on the 'stocks' that visit Australian shores.

(from Joung et. al , 1996)

The author has pledged to continue efforts to assist with the future conservation of this magnificent species. AMCS WA have indicated strong support for this initiative and have endorsed grant proposals to this end. Through extended international and national collaboration, especially via contacts gained during past and present research, new and innovative studies will be undertaken. Much of this work, however, will only be possible through the combined support of all concerned parties.

Further inquiries and information on how to assist with these efforts, please contact

Brad Norman

Australian Marine Conservation Society WA

City West Lotteries House

2 Delhi Street

WEST PERTH WA 6005

[email protected]